Evaluation of Learning

While professional learning is a requirement to keep current in any profession, within education, it is essential in the quest to improve academic achievement and transform schools. Professional learning has been thought of as an individual pursuit within the educational field. However, In recent years schools have realised that there is a need to take personal knowledge and convert it into institutional knowledge (Basten & Haamann, 2018). This paper will discuss the how and the why of learning as part of a professional learning community within an independent K-12 school context. After a brief discussion about my knowledge and understanding of professional learning within educational organisations, the strengths and weaknesses of professional conversations, in particular, my own skills will be examined. Finally, this paper will examine where my workplace is in the journey of building capacity both for professional conversations and professional learning communities, along with my growth as a leader throughout this process.

A Rationale for Professional Learning in Educational Organisations

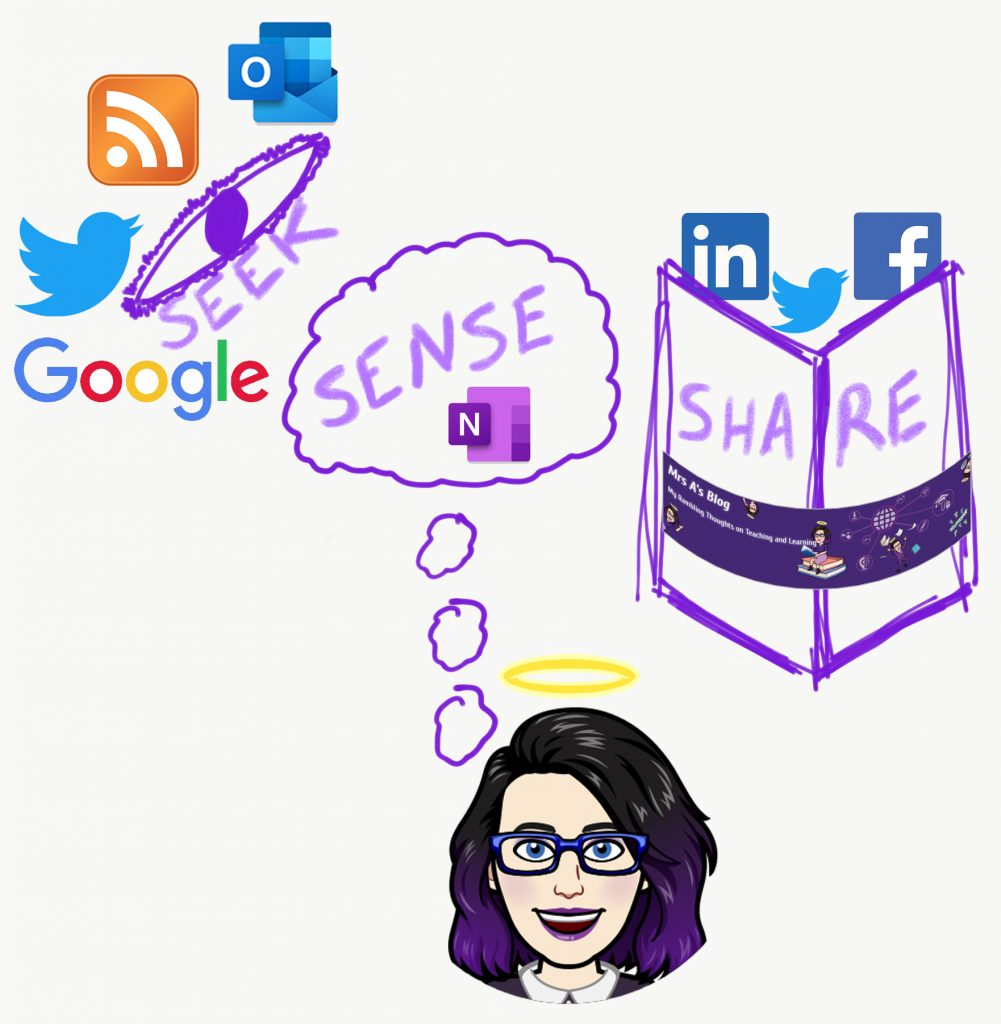

To be a successful educator, you need to commit to lifelong learning; this has been my philosophy since I started as a high school accounting and economics teacher in 2005. It has always been a personal pursuit to expand my pedagogy, ultimately to improve my students understanding, enjoyment and results within my subject areas. Since then, my journey has expanded to include a professional learning network and, more recently, the realisation that it needs to include a community of practice. I have subscribed to Jarche (2014) Personal Knowledge Mastery framework, which involves the continuous process of seeking, making sense of and sharing knowledge through networks. This is supported by Corcoran (2018), who explains that an expert network, a peer network and a transfer network are required for learning to occur. Individuals within organisations will learn even if there is no systematic learning approach (Basten & Haamann, 2018). Organisational learning aims to use targeted activities to change organisational practices (Basten & Haamann, 2018). In contrast, professional learning communities aim to use critical reflection of the human experience to create knowledge (Stoll & Kools, 2016; Vescio et al., 2008). For schools to transform, it requires school leaders to encourage the growth of the whole community if the change process is to be successful, as change requires every member to make a change (Stoll et al., 2006). Trust and respect is the centre of this process (Bradshaw & Cartwright, 2012; Carpenter, 2015; Stoll et al., 2006). Learning organisations need to take all their members’ experience, talents, and capabilities and incorporate continuous improvement (Business News Publishing, 2014; Schein, 2013). Continuous improvement cycles require the whole school to be involved in frequent and deliberate adjustments to classroom practice to transform experience into knowledge, provided that it is relevant to the organisation’s core business – teaching and learning (Schein, 2013; Senge et al., 2011; Tichnor-Wagner et al., 2017).

If schools are serious about being a learning organisation or even a professional learning community, every member of the establishment needs to be involved. An area my school struggles with is the inclusion of the leadership team within the professional learning community. Over the years, this removal from the professional learning community has led to a destructive environment that leaves teachers wondering why they bother. Carpenter (2015) suggested that this toxic culture enabled reduced job satisfaction and ineffective collaboration as teachers opted out. For professional learning communities to exist both structural (time to meet and talk, physical proximity, interdependent teaching rules, communication structures and teacher empowerment and school autonomy) and cultural conditions (social and human resources, openness to improvement, trust and respect, cognitive and skill base, supportive leadership and socialisation) need to be met (Fullan, 2006). While my workplace has successfully ensured that the structural conditions have been met, they have failed to guarantee the cultural conditions. The staff are given plenty of opportunities to hold conversations around pedagogy and research as we are all part of a single staff space. Through our appraisal system and classroom observations, staff have access to de-privatised practice and dialogic conversations where pedagogy and knowledge are shared, analysed, and refined. It falls short because the leadership team mandates it, and often staff believe that there will be punitive consequences. While a genuine sense of community exists within my department where shared values and vision, collective responsibility, and collaboration exist along with the promotion of group and individual learning, the benefits of the whole community are not supported as an entire school (Bradshaw & Cartwright, 2012; Stoll, 2012).

Evidence and Evaluation of Personal Learning

Professional learning communities are based on open and honest communication. In developing a professional learning community for this paper, a focused conversation was carried out using Conway and Andrews (2018) protocols. The protocols are based on three key aims (Conway & Andrews, 2018). Where I excelled here was around using my individual experiences to contribute to the shared meaning and respecting the contribution of others, and attempting to build on them where I struggled was around the need to balance sharing my position with inquiring into my colleagues’ views (Conway & Andrews, 2018). This was a result of being too focused on trying to make sure I shared my position. In preparation for the focused conversation, I had gathered my notes around the framework questions we had determined as a group. Unfortunately, in preparing, I had taken a more theoretical approach to the topics rather than a practical approach as the rest of the group appeared to have taken. This left me feeling unprepared for the conversation. I realise that I should have clarified this further as the conversation unfolded. As we progressed, when I got lost in the discussion, I asked group member 1 (the recorder) to revisit what had just been discussed (Conway & Andrews, 2018). As the monitor/observer, I was very aware of making sure the no blame protocol was maintained and ensuring all participants contributed (Conway & Andrews, 2018). This was accomplished by subtly asking group member 1 about her experiences in nursing without drawing attention to the fact that she hadn’t been involved in the conversation. On the other hand, I should have tried to draw group member 2 into the conversation more by interjecting at appropriate points by asking the group to open up to all contributions (Conway & Andrews, 2018). I struggled to balance the observer’s role with making sure I contributed to the conversation. Throughout the focused discussion, I learnt just how adaptable I am and how much of my experiences and knowledge were beneficial to the progression of the group understanding.

My understanding of professional learning and professional learning communities improved as the conversation progressed. Listening to the experiences of group member 1, group member 2 and group member 3 and the knowledge that they possessed has improved my comprehension of professional learning in educational organisations around establishing a professional learning community. My key takeaway was around how much organisational culture and structure affects the building of trust and respect. It was interesting that trust and respect are the keys to success in building capacity for learning within educational organisations, whether that was part of coaching and mentoring, reflective practise or the setting up of a professional learning community. The need to have buy-in at all levels of the organisation is essential for a learning organisation to flourish and have effective collaboration (Carpenter, 2015).

Discussion of Learning and Aspirations for Leading the Development of a Professional Learning Community

The continuum of professional conversation ranges from raw debate to dialogue (Conway & Andrews, 2018; Senge et al., 2011). Within my workplace, all levels of the continuum have been displayed. In professional conversations in my department, we tend to move between polite discussion and skilful discussion. While we tend to have skilful discussions when discussing our goals around feedback, collaboration, and reading comprehension, the goal is to come to an agreed census as to what this looks like in our classrooms (Conway & Andrews, 2018). On a few occasions, we have tried to conduct a focused conversation to investigate what good teaching looks like, however without an observer to draw the quieter members of the department into the conversation, the issue of ‘ping ponging’ occurred (Conway & Andrews, 2018). When the lead teachers meet, we tend to move between focused conversation and dialogue; each discussion has clear goals and involves exploration, discovery, and refining ideas and knowledge (Bohm & Nichol, 1996; Conway & Andrews, 2018). A couple of times within the secondary school, I have seen the highly adversarial raw debate occur within a professional conversation, especially when staff are passionate about the topic (Senge et al., 2011). While we all embrace professional learning as part of the requirements to remain registered teachers, most conversations are not used as a way to explore ideas and build meaning (Conway & Andrews, 2018).

Leadership and the need to build capacity for professional learning has changed within educational organisations. The traditional view of leaders is no longer the way forward; leadership no longer sits with the person at the top of the hierarchy but rather with teacher leadership (Copland, 2003; Senge, 1990; Timperley, 2012). As a leader within my school, learning to be a designer, steward and teacher will ensure that I can develop and build capacity within the professional learning community (Business News Publishing, 2014; Smith, 2001). As a designer, I must help develop shared values and vision to foster lifelong learning (Business News Publishing, 2014; Smith, 2001). Stewardship runs on multiple levels, the stewardship of people and stewardship for the larger purpose and vision once created as part of the professional learning community (Senge, 1990; Smith, 2001). The final element, leader as a teacher, refers to the coaching and facilitating of learning within the learning organisation; as part of professional conversations, it is about taking the personal knowledge and convert it into institutional knowledge (Basten & Haamann, 2018; Smith, 2001). Shared leadership is central to professional learning communities. It starts with those in senior leadership taping future leaders on the shoulder and allow them to help build the organisations capacity for professional learning within educational organisations (Carpenter, 2015; Fleming & Thompson, 2004; Timperley, 2012).

Conclusion

This paper has reflected on my knowledge and understanding of professional conversations, professional learning communities and professional learning within educational organisations. My philosophy and commitment to lifelong learning sets me up to be a leader within a learning organisation. While I still have lots to learn, I see the potential of setting up a professional learning community within my school. For it to work, both structural and cultural conditions will need to be met to ensure that the toxic culture does not develop. The benefits of having the entire school as part of the professional learning community can be experienced once these conditions exist. As I practise the protocols within my department and with the other lead teachers, my professional conversation skills will continue to improve. As I continue to develop as a leader, these skills will become more of a part of my practice.

References

Basten, D., & Haamann, T. (2018). Approaches for organisational learning: A literature review. SAGE Journals, 8(3). https://doi.org/10.1177/2158244018794224

Bohm, D., & Nichol, L. (1996). On dialogue. Routledge.

Bradshaw, P., & Cartwright, M. (2012). Leading professional practice in education. SAGE Publications Ltd.

Business News Publishing. (2014). Summary: The fifth discipline: Review and analysis of Senge’s book. Lemaitre Publishing. http://ebookcentral.proquest.com/lib/usq/detail.action?docID=2080359

Carpenter, D. (2015). School culture and leadership of professional learning communities. International journal of educational management, 29(5), 682-694. https://doi.org/10.1108/IJEM-04-2014-0046

Conway, J., & Andrews, D. (2018). Time to talk – The LRI handbook for facilitating professional conversation. Leadership Research International (LRI), University of Southern Queensland. https://usqstudydesk.usq.edu.au/m2/mod/equella/view.php?id=1858313

Copland, M. A. (2003). Leadership of inquiry: Building and sustaining capacity for school improvement. Educational evaluation and policy analysis, 25(4), 375-395. https://doi.org/10.3102/01623737025004375

Corcoran, B. (2018). Education’s Latest Secret Trend: Networking. EdSurge. https://www.edsurge.com/news/2018-08-14-education-s-latest-secret-trend-networking

Fleming, G. L., & Thompson, T. L. (2004). The role of trust building and its relation to collective responsibility. In S. M. Hord (Ed.), Learning together, leading together: changing schools through professional learning communities. Teachers College Press.

Fullan, M. (2006). Leading professional learning. School Administrator, 63(10), 10-14. https://www.proquest.com/trade-journals/leading-professional-learning/docview/219287566/se-2?accountid=14647

Hallam, P. R., Hite, J. M., Hite, S. J., & Mugimu, C. B. (2012). Trust and educational leadership: Comparing the development and role of trust between US and Ugandan school administrators. In C. Wise, M. Cartwright, & P. Bradshaw (Eds.), Leading professional practice in education (pp. 71-86). SAGE Publications. http://ebookcentral.proquest.com/lib/usq/detail.action?docID=4853823

Jarche, H. (2014). What is your PKM routine? Jarche. Retrieved 5 March 2020 from http://jarche.com/2014/03/what-is-your-pkm-routine/

Jarrett, K., Cooke, B., Harvey, S., & Lopez-Ros, V. (2021). Using professional conversations as a participatory research method within the discipline of sport pedagogy-related teacher and coach education. Journal of Participatory Research Methods, 2(1). https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.35844/001c.18249

Schein, E. H. (2013). Humble inquiry: The gentle art of asking instead of telling (1st ed. ed.). Berrett-Koehler Publishers, Inc.

Seashore Louis, K. (2006). Changing the culture of schools: Professional community, organisational learning, and trust. Journal of school leadership, 16(5), 477-489. https://doi.org/10.1177/105268460601600502

Senge, P., Kleiner, A., & Roberts, C. (2011). Fifth discipline fieldbook: Strategies for building a learning organisation. Nicholas Brealey Publishing. http://ebookcentral.proquest.com/lib/usq/detail.action?docID=753392

Senge, P. M. (1990). The leaders new work: Building learning organisations. Sloan Management Review, 32(1), 7-23.

Smith, M. K. (2001). Peter Senge and the learning organisation. The Encyclopedia of Pedagogy and Informal Education. https://infed.org/mobi/peter-senge-and-the-learning-organization/

Stoll, L. (2012). Leading professional learning communities. In C. Wise, M. Cartwright, & P. Bradshaw (Eds.), Leading professional practice in education (pp. 234-247). SAGE Publications. http://ebookcentral.proquest.com/lib/usq/detail.action?docID=4853823

Stoll, L., Bolam, R., McMahon, A., Wallace, M., & Thomas, S. (2006). Professional learning communities: A review of the literature. Journal of educational change, 7(4), 221-258. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10833-006-0001-8

Stoll, L., & Kools, M. (2016). What makes a school a learning organisation? OECD Education Working Papers, 137. https://doi.org/10.1787/5jlwm62b3bvh-en

Tichnor-Wagner, A., Wachen, J., Cannata, M., & Cohen-Vogel, L. (2017). Continuous improvement in the public school context: Understanding how educators respond to plan–do–study–act cycles. Journal of educational change, 18(4), 465-494. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10833-017-9301-4

Timperley, H. (2012). Distributing leadership to improve outcomes for students. In C. Wise, M. Cartwright, & P. Bradshaw (Eds.), Leading professional practice in education (pp. 148-161). SAGE Publications. http://ebookcentral.proquest.com/lib/usq/detail.action?docID=4853823

Timperley, H. (2015). Professional conversations and improvement-focused feedback: A review of the research literature and the impact on practice and student outcomes. Australian Institute of Teaching and Scool Leadership.

Vescio, V., Ross, D., & Adams, A. (2008). A review of research on the impact of professional learning communities on teaching practice and student learning. Teaching and Teacher Education, 24(1), 80-91. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tate.2007.01.004